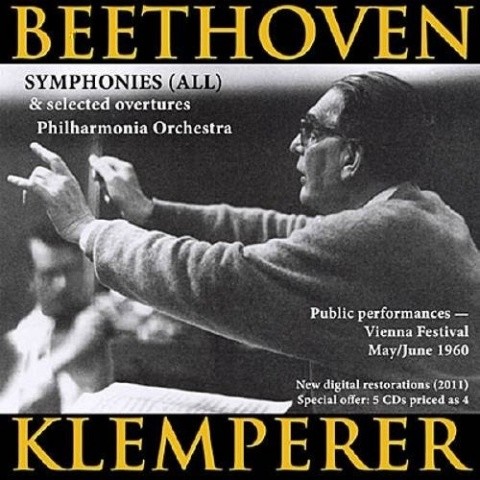

Klemperer Conducts Beethoven: Symphonies (All) & Selected Overtures

克伦佩勒1960年指挥爱乐乐团在维也纳音乐节表演的贝多芬九首交响曲和三首序曲。

BEETHOVEN Symphonies 1–9. Overtures: Coriolan; Egmont; Prometheus • Otto Klemperer, cond; Wilma Lipp (sop); Ursula Boese (alt); Fritz Wunderlich (ten); Franz Crass (bs); Vienna Singverein; Philharmonia O • MUSIC & ARTS 1252, mono (5 CDs: 389:06) Live: Vienna 5–6/1960

This cycle was previously released by Music & Arts in 1995, but these are completely new transfers by Aaron Snyder. So the first question is how they compare, and whether the difference merits replacement of the old edition, for those who already own it. The answer is an emphatic yes: The sound, dry and boxy in 1995, has been dramatically improved in presence, warmth, and sense of the hall (Musikverein)’s acoustic. Bravo Mr. Snyder!

The set is valuable for being the only record on CD of an integral live Beethoven cycle by Klemperer. Of course there are many live alternatives for individual symphonies, and Klemperer aficionados will naturally have different opinions over which version is best. Klemperer was nearly always more compelling live than in the studio, and while individual performances in this 1960 cycle may be surpassed by other live versions (more on that below), it is still consistently preferable to the EMI recordings of 1957–59. The concerts were given over a few days from late May to early June. The occasion of Klemperer’s return to Vienna was a special one, and the audience’s keen anticipation, rapt concentration, and spontaneous appreciation are vividly conveyed (applause is retained before and after each work, conveniently tracked separately). The Philharmonia knew Klemperer’s interpretations like the back of their collective hand by this time, and their playing is consistently at the highest levels of subtlety, refinement, and concentration. The old canard that Klemperer was unconcerned with beautiful sound, uncritically repeated in the (generally rather lazy and cliché-ridden) notes to this set, really does not survive scrutiny; his concern for the right balance and quality of sound was obsessive, and is everywhere in evidence here. The performances are exceptionally compelling, full of fascination in every bar, even when ensemble is less than ideally tidy at tempos that can be provocatively deliberate (which, Klemperer being himself, is often!). For all their complete absence of interpretive ego or striving for effect, these are immensely eventful readings, less monolithic than the EMI accounts, and with a spontaneously re-creative feel that their studio counterparts rarely hint at.

No. 1: The slow introduction goes at a good clip, as was Klemperer’s wont, but he miscalculates the beginning of the Allegro con brio , which he launches too fast before settling back to his comfort zone; second time through the exposition, the tempo has very noticeably dropped from 104 to 92 (for his time, Klemperer was more generous than most with exposition repeats; in this symphony, all three are observed). In the introduction to the finale, Klemperer’s beat was evidently uncertain—the concertmaster is audibly holding things together by playing loudly, discreetly followed by a tentative violin section; and the tricky leadin to the Allegro molto e vivace is slack and uncoordinated. But for the most part the playing is refined and polished, phrasing wonderfully lucid. Nothing is overlooked, with keenly observed accents and dynamic distinctions really registering at Klemperer’s unhurried pace.

No. 2: Klemperer’s tempo choices are (even) more-than-usually controversial here—the first movement’s Allegro con brio is very leisurely, though pointed and alert; his dogged pace in the finale is hard to square with Beethoven’s prescribed Allegro molto , though the coda still manages to generate real excitement. The Larghetto is slow and lovingly detailed, with (as so often in this cycle) a wonderful chamber-like feeling of the players really listening to one another.

No. 3: The “Eroica” always brought out the best in Klemperer, and this one is no exception. Much of the first movement’s exposition has an expansive, lyrical feel, and the development unfolds with remarkable translucent clarity. But the long-range control is masterly, and the coda has great cumulative power, with a subtle upping of the tempo for the final gradual buildup. Klemperer never neglected the march in the Marcia funebre, which has a wonderfully sustained momentum at a more flexible tempo than his studio accounts. The Trio of the Scherzo is another highlight, with exceptionally beautiful and characterful horn playing. After a slow start, the finale’s variations build tremendous intensity. The Poco andante interlude (bars 349 ff.) is unforgettable—the climactic statement of the theme luminously radiant; then in the dissolution to expectant tension before the final Presto , a truly breathtaking fine-tuned calibration of orchestral response.

No. 4: The Adagio introduction is another of those passages Klemperer habitually took surprisingly fast, and is disconcertingly slack here; as in No. 2, the first-movement Allegro (vivace) feels too leisurely, although with a compensating poise and lucidity. The slow movement again has a memorable chamber-like delicacy; the Scherzo, though characterful and spirited, has a slightly galumphing effect at Klemperer’s tempo. Although he honors the “ma non troppo” qualification of the finale’s Allegro with a vengeance, the unusually deliberate tempo is put to good use, in a rare trenchant clarity of articulation. Both outer-movement exposition repeats are observed.

No. 5: The first movement is steady and controlled, perhaps not Klemperer’s most exciting version, but with a fine cumulative impact, notwithstanding a rather exasperating tendency to shortchange Beethoven’s strictly notated rests. In the development, Klemperer goes to obsessive lengths in his care over audibility of everything in the texture—e.g., in bars 180 ff., the way he sharply pulls the strings back from their notated ff to bring out the rhythmic woodwind figure. The Andante is beautiful, though the sudden tempo increase after the second variation (bars 124 ff.) feels a little unmotivated. The deliberate tempo works well in the Scherzo, which has great trenchancy and grip, but less well for the Trio, which has a rather ponderous feel. In the finale, Klemperer is perhaps a trifle stolid (though he was one of the few conductors of his generation to take the exposition repeat), but builds real excitement in the coda.

No. 6: Our arrival in the countryside is patient and leisurely (enhanced by the exposition repeat), with all the time in the world for finely observed scenic details (a richly singing second theme, and delicately precise closing section). I have more mixed feelings, though, about the “Scene by the Brook,” which is paradoxically bedeviled by both rhythmic approximation (e.g., the sudden unmotivated lurch forward at bar 13, and uncertain strings/woodwind coordination throughout) and an insufficient rhythmic variety, with too little artful variation of the pulse to keep up the tension (something Furtwängler and Mengelberg both excelled at). As always with Klemperer, the Scherzo is eccentrically slow, but the “Storm,” after getting off to a tentative start, then inspires a truly elemental outpouring of tone. The “Shepherd’s Hymn” was always a Klemperer highlight, and this one is utterly glorious, with electrifying rhythmic articulation from the strings, and building to an unforgettably resplendent translucence.

No. 7: Klemperer’s Seventh has often suffered a bad critical press for his slow tempos in this most dance-like of symphonies, but on this occasion he really achieved liftoff. Following a beautifully balanced introduction, the Vivace goes with a measured Schwung, not without some moments of rhetorical exaggeration—e.g., his massive deliberation in the “echoing” chords effect, bars 124 ff. In the development, I have rarely if ever heard such tremendous bite from the canonic string writing at bars 201 ff., and the coda has a fierce exaltation. The Allegretto possesses a grave beauty, not too slow (at 9:29, Klemperer is in no danger of breaking any speed records, but this is hardly the “funeral march” alluded to in the notes), though the major-mode contrast brings another of his disconcerting lurches in tempo. Although the Scherzo’s deliberation may seem to border on perverse, it is salvaged (as so often) by the Philharmonia’s exceptional rhythmic alertness, and the Trio has an arrestingly beautiful simplicity. Similarly, Klemperer’s dogged, weighty conception of the finale may disconcert at first, but he makes it work by virtue of the merciless contrapuntal clarity uncovered. The end of the exposition and recapitulation bring playing of astonishing vehemence from the second violins and violas, which Klemperer goads to a seemingly superhuman crescendo. The coda’s sinking string exchanges have an x-ray clarity, and the chromatic bass ostinato (E–D?) supporting the climactic appearance of the main theme has rare force and presence. The end is phenomenally exciting—this is altogether unforgettable!

No. 8: Klemperer’s conception of this symphony is bigger and more massive than most, with an uncompromising deliberation that avoids heaviness through razor-sharp rhythmic acuity. It’s certainly characterful—hear the awesome juggernaut of the approach to the first movement’s recapitulation, the surprisingly fierce edge he imparts to the forte passages of the Allegretto scherzando, or those assertively gruff cellos in the Minuet’s Trio. The finale has forceful clarity and point, though the unhurried pace inevitably sacrifices much of the music’s (necessary) ingredient of madcap dash.

No. 9: Klemperer saves the best for last, in an inspirational culmination to the cycle. The opening is given unusually free treatment, indistinct at a very flexible tempo, but expressively molded in the violins’ motive. The second theme’s intricate contrapuntal textures are shaped with great individuality, at a flexibly breathing pace and with marvelous textural transparency (hear the slow buildup from pp, bars 120 ff.). The major-mode beginning to the recapitulation is a telling object lesson in the deceptive simplicity of Klemperer’s seeming objective literalism—truly elemental power, but artfully enhanced by carefully manipulated textural balances. The Scherzo is measured, but not slow, with an iron grip and uniquely Klempereresque details—hear the inimitable way he brings out the rising tonic triad as a hocket effect from the horn parts (bars 44 ff.). The Adagio is lucid and refined, at a tempo surprisingly fast for its day (14:06; among the old-school conductors, Klemperer and Toscanini were two who instinctively got the tempo right in this movement). The finale possesses great sweep, power, and clarity, Klemperer inspiring his orchestral and vocal forces to great heights of expressive fervor. The women soloists are smooth and rich; Fritz Wunderlich his usual incomparable self, Franz Crass characterful though somewhat brittle.

Overtures: In Egmont, the main Allegro is rather slow and lumbering, but Klemperer makes amends in a powerful, finely shaped Victory Symphony. There’s an ear-catching detail at the very end, in his lengthening of the piccolo notes (high Fs) for added force and penetration—the distinctive “Klemperer sound” owed much to his penchant for bringing out textural extremes; at the other end of the spectrum, witness the exceptional presence and expressive engagement of the basses throughout this cycle. Prometheus has rarely been invested with such massive power, trenchantly articulated. Coriolan is gripping in its combination of implacable objectivity and classical restraint, at the same time full of subtle nuance, as in the distinctively “drained” tone color he draws from the violins in the last (C Major) appearance of the second theme before the final catastrophe.

Finally, I should note that these performances, for all their unique qualities and insights, would not be my first choices among available live Klemperer versions; my vote would go to another Philharmonia cycle, the Royal Festival Hall one from 1957, with performances consistently faster and tauter than the present ones. But unfortunately it’s not complete; Testament has released Nos. 2, 4, 5, 7, and 9 only. This Vienna cycle has a coherent feel to it, a real sense of journey from beginning to end, and on that account makes for a uniquely satisfying listening experience.

FANFARE: Boyd Pomeroy